Star Wars Philosophy: Luke Skywalker, Zen Master

Three ways The Last Jedi illustrates Zen Buddhism

Released in 2017, Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi is the most divisive of all Star Wars films. Some see it as a nihilistic and destructive film. I would argue that its predecessor The Force Awakens is actually more destructive, in undoing everything accomplished by the original heroes to plunge the galaxy into almost exactly the same state. The Last Jedi is just where those ill-conceived chickens come home to roost, but the result is IMO actually a pretty beautiful film.

Much of the criticism towards TLJ is directed at the portrayal of Luke Skywalker. The idealistic man who would dash in to save his friends, and who insisted there was good in Darth Vader, has become a bitter recluse who catalysed his nephew’s fall to the dark side by a kneejerk lightsaber ignition. People are divided over whether this is in character; I think it is (given the events that have occurred), but the real problem is that when this is the only time we get to spend with a beloved hero after 30 years, it is a depressing direction for the story to go in (albeit with a powerful payoff in the third act).

Recently, as I’ve been studying Zen, I’ve found that a lot of what we see with Luke is quite helpful for illustrating aspects of Zen. Luke intended to teach Rey three lessons, so here are three things TLJ shows us about Zen:

1) Luke’s lightsaber toss is like a Zen Koan

We all know the moment. Rey hikes to the top of the island and we get our first glimpse of Luke Skywalker since 1983. She hands him his father’s lightsaber, and what does he do with this sacred totem?

He tosses it behind him and strides away.

Was this a cheap laugh, as part of Rian Johnson’s oh-so-clever desire to subvert our expectations? I don’t think so. I think Luke does it out of deep sadness and wariness.

Insofar as Rey holding out the saber is posing a question (“legendary Jedi, will you pick up Excalibur and help vanquish the darksiders?”), Luke throwing it is an answer. But it’s not a literal “no I won’t” reply. It’s more “you’re asking the wrong question.” And that’s what makes this a lot like a Zen Koan.

Koans are philosophical vignettes that have been used for over a thousand years to get students out of their habitual logical thinking. They tend to be anecdotes of interactions between masters and students, where a student often asks a question, and the master says or does something baffling—like saying nonsense words, walking away, or even slapping the student.

A couple of examples:

A monk asked, “What is the absolute reality of the Buddha?”

The master said, “Is there anything else you don’t like?”

A monk asked, “What is the Way?”

The master said, “You’re too kind!”

(From The Recorded Sayings of Joshu (translation by Green)).

In both cases, the master is not answering the question. Instead, he’s seeing what state of perception the student is in that has prompted the question, and he replies in his own state of perception in a way that makes the student hit a wall, and forces them to break through their habitual logical thinking.

My interpretation of the first one is that the monk is only asking what absolute reality is, because he isn’t content to see everything around him as such. So the master thinks, well you wouldn’t ask this if you didn’t feel that way, so what else are you unsatisfied about?

In the second, I think the master is replying to the flattering implication of the monk’s question—that he thinks the master knows what the way is.

"The fish trap exists to catch the fish. Once you have the fish, you can forget the trap. Words exist to catch the meaning. Once you have the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words so I can talk with him?" - 4th century BCE Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi.

Let’s go back to Luke. Rey hands him the saber, asking him to take up his lost weapon and join the fight. Luke throwing the saber is saying, this thing is useless. Everything you think you know about the Jedi is wrong.

Or perhaps Luke throws the saber is because that’s exactly what being a Jedi means (at least in the koan poetic sense). Remember the last time he threw a lightsaber away? The most powerful moment in the whole of Star Wars?

For him, that was the epitome of embodying a Jedi. So for this noob to come and ask him to fight with his laser sword is completely missing the point. And in the end, Luke demonstrates his understanding of the Force better than anybody, by saving the Resistance on Crait as a Force projection, appearing to Kylo Ren to distract him in a battle where he’d otherwise have had to kill him.

Now, Luke wasn’t intending to teach Rey in the moment he tossed the saber. It was an instinctual reaction. But I’m not sure he could have reacted any other way. And the film is so meta, perhaps the koan is directed at us.

In a deleted scene, when Luke is training Rey, he really messes with her mind:

2) Masters can be asshats

The Last Jedi is all about a main character looking to a heroic teacher figure to guide her, and he can’t give her the answers she needs. She has to make her own choices—and her own mistakes.

Not every teacher is like Alec Guinness’s Obi-Wan, kindly and (seemingly) wise. Zen Koans are replete with instances of masters being rude, unkind and mean. The influential master Joshu, when asked by a student “what are honest words?” replied, “Your mother is ugly.”

The Last Jedi’s Luke is a bitter, highly flawed man. On the one hand this is quite a brave creative portrayal, on the other it is a pretty sad way to show the later years of a beloved character we’ve been waiting decades to see again.

But Zen’s portrayal of masters as flawed, abrasive people is a helpful reminder that no teacher is perfect. You have to form your own compass.

“We are what they grow beyond,” Yoda says. “That is the true burden of all masters.”

Not even the Buddha is exempt from this: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him,” an old koan says. Don’t look outside yourself for the answers.

3) Nothing is sacred

That’s another thing with Zen: because it’s ultimately about mastery of your mind, there is little space for putting anything or anyone on a pedestal. Unlike religions, Zen has no prescribed holy text, authority or bible.

In his Introduction to Zen Buddhism, D.T. Suzuki writes:

When Tokusan gained an insight into the truth of Zen he immediately took out all his commentaries on the Diamond Sutra, once so valued and considered indispensable that he had to carry them wherever he went, and set fire to them, reducing all the manuscripts to ashes.

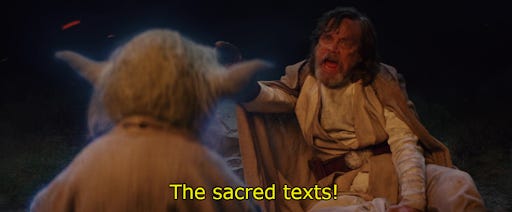

Yoda sets fire to the tree containing the Jedi texts, leading Luke to cry out at the destruction of these hallowed papers. They haven’t been destroyed, we later learn, but Luke doesn’t know that. Yoda’s reminding him that he needs to trust himself rather than some dogma. Failing to do that is what did the Jedi in to begin with.

And failure is a big theme of the film: “The greatest teacher, failure is,” says Yoda. It’s something I think the film explores really well.

I’ll be diving further into Zen and Koans with my upcoming podcast Koanversation. Subscribe to stay updated!